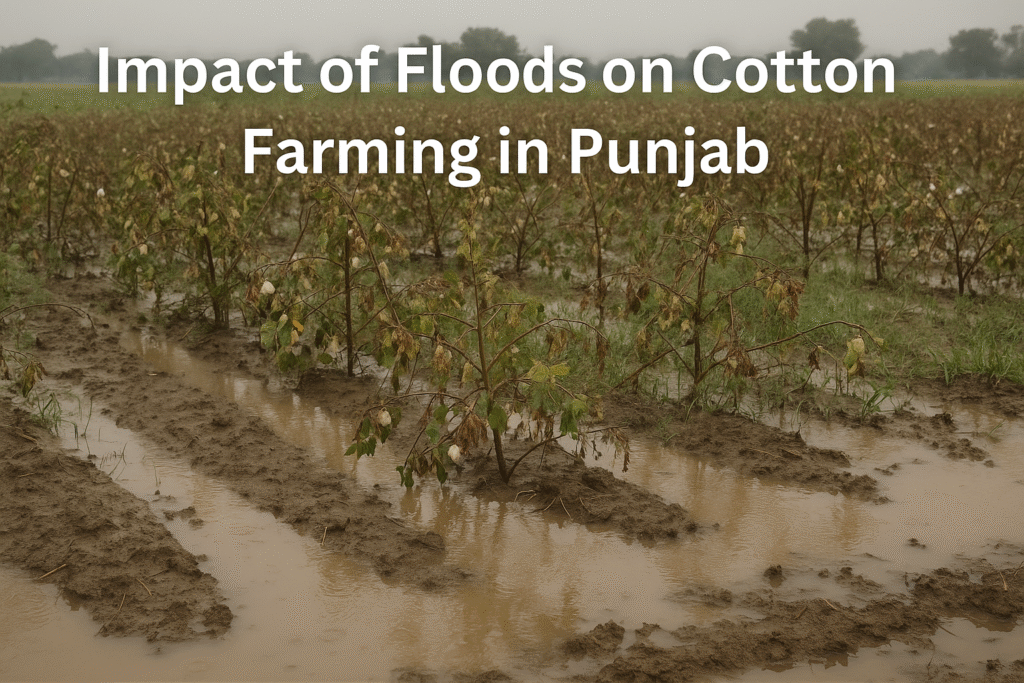

Kapas ki kheti (cotton farming) stands as one of Punjab’s most valuable cash crops, sustaining thousands of farming families and feeding the backbone of the textile industry. Yet, the recent floods have pushed this sector into a state of crisis. Torrential rains and overflowing rivers have drowned vast stretches of farmland, turning fertile fields into swamps. The prolonged waterlogging has not only destroyed standing cotton crops but has also created deep uncertainty about the upcoming harvest. For farmers who rely almost entirely on kapas ki kheti for their livelihood, the devastation has brought both financial instability and emotional distress, threatening the future of cotton farming in the region.

Present Condition of Farmers

1. Severe Crop Destruction: In Punjab’s cotton belt covering districts like Bathinda, Mansa, Fazilka, and Muktsarfarmers are witnessing unprecedented losses. Entire stretches of kapas ki kheti have been submerged under floodwater for days, causing cotton plants to wither and rot. Once-healthy green fields are now waterlogged wastelands, leaving cultivators uncertain about whether they will harvest even a fraction of their expected yield. For many, this season’s cotton crop is already a total write-off.

2. Mounting Financial Strain: Kapas ki kheti demands heavy upfront spending on hybrid seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, and labor. With standing crops destroyed, farmers are unable to recover these costs. While the government has announced ₹20,000 per acreas compensation for severely damaged fields, cultivators argue it barely covers half of their real expenditure. For small and marginal farmers who depend solely on cotton income, the mismatch between losses and relief has left them financially crippled, deepening the cycle of debt.

3. Collateral Damage to Infrastructure: The devastation extends far beyond crop loss. Floodwaters have destroyed tubewells, irrigation channels, bunds, and farm machinery, further straining farmers’ resources. Repairing this infrastructure will require additional investment at a time when farmers are already cash-strapped. Many are also under pressure to repay loans taken for this season’s cotton cultivation, while simultaneously preparing fields for the Rabi season a nearly impossible task without adequate support.

Impact of Floods on Kapas ki Kheti

1. Waterlogging and Crop Failure: Cotton is highly vulnerable to excess water because its root system requires proper aeration to grow. In Punjab’s flood-hit districts, kapas fields remained submerged for more than 48–72 hours, leading to root rot, wilting, and premature plant death. Unlike paddy, which thrives in water, cotton cannot tolerate prolonged submersion. This has turned large areas of productive land into unharvestable wastelands. Farmers report that even fields where plants survived show stunted growth and poor boll formation, making recovery nearly impossible.

2. Spread of Pests and Diseases: Flood conditions have created a breeding ground for fungal infections, boll rot, andsucking pests like whiteflies. Continuous moisture weakens the plants, leaving them highly susceptible to infestations. Farmers in BathindaandMansa are noticing yellowing leaves, leaf spots,and rotting bolls, which drastically reduce both the quantity andquality of kapas fibre. Lower-quality cotton fetches poor prices in the market, further deepening farmer losses. The rise in pests also forces farmers to spend more on pesticides, increasing costs at a time when their incomes are already collapsing.

3. Reduced Acreage and Output: Kapas ki kheti in Punjab has been on a steady decline due to climate change, pestattacks, and shifting crop preferences. This year, the acreage was already down to 1.19lakh hectares, the lowest in decades. Floods have worsened the situation by destroying more than 30,000 acres of standing cotton, pushing production further down. The fall in acreage and output not only hurts farmers’ incomes but also poses a serious challenge to Punjab’s textile mills, which depend heavily on locally grown cotton. If this trend continues, the state’s cotton economy may face long-term disruption.

4. Price Pressure Due to Imports: While local kapas production is falling, the government has allowed duty-free cottonimports until 2025 to ensure that textile industries do not face raw material shortages. Although this move benefits textile manufacturers, it creates severe pressure on domestic farmers. Imported cotton, being cheaper, reduces the market price of local kapas, leaving farmers with lower returns despite higher production costs. At a time when floods have already destroyed crops and increased financial stress, this policy adds to farmers’ distress, making it harder for them to recover from losses.

Challenges in Recovery After Floods

1. Silt and Debris Overload: When floodwaters recede, they leave behind heavy deposits of sand, silt, and debris across farmland. This layer suffocates the soil by blocking aeration and reducing its natural fertility. If not removed in time, the soil structure hardens, making it unsuitable for seed germination. For kapas ki kheti and upcoming crops alike, this poses a major obstacle. Farmers must now invest extra effort and money in clearing fields before they can even begin preparing for the next cycle of cultivation.

2. Narrow Window for Sowing: Time is one of the biggest enemies after floods. Farmers have a very short window to prepare their land for the Rabi season, especially for wheat, which must be sown on time to ensure good yields. Every delay in draining water and clearing silt pushes sowing further back, leading to lower productivity. This creates a chain reaction oflosses, as missing one season reduces not only income but also the ability to invest in the next crop cycle.

3. Limited Relief and Support Gaps: Although initiatives like “Jehda Khet, Ohdi Ret” have eased rules by allowing farmers to clear flood deposits without lengthy government approvals, the ground reality remainsharsh. Most small and marginal farmers lack access to heavy machinery such as tractors with loaders or earthmovers needed for silt clearance. Hiring such equipment is costly, and with already depleted finances, many cultivators simply cannot afford it. Without timely and practical support, restoring farmlands remains out of reach for thousands of farmers

Government and Policy Response

To address the devastation caused by floods, the Punjab government has rolled out several measures aimed at supporting farmers. A compensation package of ₹20,000 per acre has been announced for crops that have suffered 75–100% damage, offering some relief to cotton cultivators. Additionally, the state has sought ₹151 crore under the Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY) to assist with silt removal and soil restoration, as floodwaters have left behind thick layers of sand and debris that threaten the fertility of farmland. In a further step, authorities have waived the requirement for a No Objection Certificate (NOC) in certain districts, allowing farmers to clear flood deposits without bureaucratic delays. However, despite these initiatives, many farmers argue that the compensation is too little, arrives too late, and does not reflect the actual scale of their losses. They continue to demand faster, fairer, and more comprehensive support systems to recover from this crisis.

Future of Kapas ki Kheti in Punjab

1. Improved Drainage Infrastructure: One of the biggest lessons from the recent floods is the urgent need for a stronger drainage system in cotton-growing areas. Poorly maintained canals and village drains often cause water to stagnate in fields, leading to crop failure. By investing in moderndrainage networks, rainwater harvesting, and desilting of canals, the state can ensure that excess water is quickly diverted, preventing large-scale waterlogging that harms kapas crops.

2. Climate-Resilient Practices: Kapas ki kheti in Punjab has become increasingly vulnerable to climate change,unpredictable monsoons, and pest outbreaks. To address this, agricultural research institutions need to promote flood-tolerant, drought-resistant, and pest-resistantvarieties of cotton. Alongside this, adopting crop diversification and integrated pest management will make farming more sustainable, reducing the risk of total crop loss during extreme weather events.

3. Soil Health Restoration: Floods often leave behind silt, sand, and chemical imbalances in farmland, reducing fertility and lowering yields. To rebuild soil health, farmers should be supported with machinery for silt removal, subsidies for organic inputs like compost and greenmanure,and soil testing services. Over time, such measures will restore productivity, ensuring that kapas ki kheti remains viable even after repeated natural shocks.

4. Fair Pricing Policies: Market fluctuations and cheap cotton imports often reduce the income of Punjab’s cotton farmers. To protect them, the government must guarantee a Minimum SupportPrice (MSP) for kapas or intervene in the market to stabilize prices. This will ensure that farmers receive fair returns on their investment, even when international prices are lower. A fair pricing system will also encourage more farmers to continue cultivating cotton, preventing further decline in acreage.

5. Crop Insurance and Early Warning Systems: Floods, pests, and extreme weather will remain recurring challenges. To reduce risks, expanding crop insurance coverage for kapas farmers is essential. Affordable and accessible insurance schemes can compensate farmers for unforeseen losses. In addition, setting up real-time weather forecasting and early warning systems at the village level can help farmers take timely precautions, such as draining fields or applying protective sprays, before damage occurs.

Final Thought

Floods in Punjab have devastated kapas ki kheti, destroying crops and leaving farmers in crisis. While relief offers temporary help, long-term solutions like better drainage, soil restoration, and fair pricing policies are essential to secure the future of cotton farming in the state. Without strong action, farmers will remain trapped in debt and uncertainty. Protecting kapas ki kheti is not just about crops it is about safeguarding livelihoods and sustaining Punjab’s rural economy.

FAQs

1. How have floods affected kapas ki kheti in Punjab?

Ans: Floods have submerged thousands of acres of cotton fields, causing waterlogging, root damage, and crop failure. Many farmers have lost their entire harvest.

2. Which districts of Punjab are most affected by flood damage to cotton?

Ans: The worst-hit districts include Bathinda, Mansa, Fazilka, and Muktsar, where large areas of kapas fields have been destroyed.

3. Why is cotton farming (kapas ki kheti) so vulnerable to floods?

Ans: Cotton plants cannot survive in standing water for more than 48–72 hours. Excess moisture leads to root rot, fungal infections, and pest outbreaks, making the crop highly flood-sensitive.

4. What financial support has the government announced for affected farmers?

Ans: The Punjab government has announced ₹20,000 per acre compensation for 75–100% crop loss and sought funds for silt removal under RKVY. However, farmers feel this is insufficient.

5. How are cotton imports affecting local kapas farmers in Punjab?

Ans: The government has allowed duty-free cotton imports until 2025. While this supports the textile industry, it lowers domestic prices, reducing farmer profits during an already difficult season.

6. What steps can secure the future of kapas ki kheti in Punjab?

Ans: Key measures include better drainage infrastructure, flood-tolerant cotton varieties, soil health restoration, fair pricing through MSP, and expanded cropinsurance.